Page 1

1.

When measuring real purchasing power parity (PPP) between China and the United

States, prices of goods measured in dollars at the exchange rate in both nations resulted

in:

A)

higher prices for goods in China compared with the United States.

B)

lower prices for goods in China compared with the United States.

C)

prices of goods that were roughly equal.

D)

Chinese customers having higher incomes in terms of purchasing power.

2.

Purchasing power parity (PPP) in the goods markets would hold if all goods were:

A)

manufactured domestically.

B)

inspected at the ports.

C)

freely tradable.

D)

traded only domestically.

3.

Arbitrage occurs when an entity purchases a good in the lower-priced market and sells it

at the same time in the higher-priced market. The existence of trade costs would ____

opportunities for arbitrage.

A)

lower

B)

not affect

C)

increase

D)

completely eliminate

4.

Arbitrage may not achieve purchasing power parity due to:

A)

trade costs.

B)

dealer markups that vary between nations.

C)

taxes on income.

D)

high interest rates.

5.

When there are no trade costs, which of the following conditions exist?

I. There is no arbitrage.

II. The law of one price (LOOP) is operational.

III. The real exchange rate is equal to one.

A)

I

B)

II

C)

I and II

D)

II and III

Page 2

6.

The United States and Mexico can each produce automobiles for $20,000 and 230,000

pesos (P), respectively. Based on the information provided, will the United States be

able to export automobiles to Mexico if the exchange rate is P10 = $US1, and trade

costs are 10%?

A)

Yes, its price advantage more than offsets trade costs.

B)

No, its price advantage does not offset trade costs.

C)

No, its price advantage equals trade costs.

D)

Yes, because trade costs are only a very small share of the price.

7.

The United States and Mexico can each produce automobiles for $20,000 and 230,000

pesos (P), respectively. Suppose that Mexican auto producers decide to lower their price

to begin selling in the U.S. market. Given trade costs of 10%, what is the maximum

price they can establish (net of trade costs) that will allow them to sell Mexican autos at

the same price as U.S. autos?

A)

P200,000

B)

P220,000

C)

P180,000

D)

P181,818

8.

The United States and Mexico can each produce automobiles for $20,000 and 230,000

pesos (P), respectively. Suppose that U.S. auto producers decide to raise prices to take

advantage of their comparative advantage. What is the maximum price that they can

establish (net of trade costs) that will just allow them to sell U.S. autos at the same price

as Mexican-produced autos?

A)

$20,000

B)

$18,000

C)

$21,000

D)

$20,909

9.

Consider the following information about prices: P = $150; EP* = $180. If the cost of

transporting the product is $15, then the real exchange rate is:

A)

1.

B)

1.20.

C)

1.75.

D)

1.33.

Page 3

10.

Consider the following information about prices: P = $150; EP*= $180. If the cost of

transporting the product is $15, based on this information:

A)

it is possible to engage in arbitrage.

B)

it is not possible to engage in arbitrage.

C)

it is inconclusive whether arbitrage is possible.

D)

arbitrage is possible only if transportation cost is $1.

11.

The no-arbitrage band delimits the:

A)

range in which profitable trading can occur.

B)

deviation from 1 that the real exchange rate may exhibit.

C)

additional fees charged to exchange currency.

D)

propensity of governments to impose trade restrictions.

12.

In general, if the trade costs are higher, the existence of PPP and the LOOP are:

A)

more likely.

B)

impossible.

C)

less likely.

D)

irrelevant.

13.

Consider the following information about prices, P = $150; EP*= $180. If the cost of

transporting the product is $15, the no-arbitrage band is within the limits of:

A)

0.91–1.2.

B)

0.99–1.01.

C)

0.91–1.1.

D)

1–1.5.

14.

A recent study concluded that trade costs for advanced countries represent about a

______ markup over the pre-shipment price of the goods.

A)

10%

B)

25%

C)

50%

D)

75%

15.

Which of the following will increase trade costs?

A)

an increase in tariff rates in the importing country

B)

a reduction in quotas in the importing country

C)

a decrease in transportation costs

D)

a decrease in the importing country's exchange rate

Page 4

16.

Trade costs can vary from one nation to another. All of the following tend to increase

trade costs, EXCEPT:

A)

reduction of quota limits on imports.

B)

increased regulatory barriers.

C)

higher transportation costs.

D)

more liberalized trade.

17.

Consider the following information about prices, P = $150; EP* = $180. If the cost of

transporting the product is $30, then the LOOP suggests that:

A)

there is no room for arbitrage.

B)

the arbitrage band is between 0.91 and 1.1

C)

there is significant profits to be made from arbitrage.

D)

the arbitrage band is between 0.2 and 1.8.

18.

International trade costs consist of:

A)

transport costs.

B)

costs at the border.

C)

labor costs.

D)

transport costs and costs at the border.

19.

Increasing trade costs:

A)

result in a narrower arbitrage band.

B)

exist in advanced countries.

C)

result in a wider arbitrage band.

D)

promote increased volume of trade.

20.

The Big Mac index illustrates that in lower-income nations:

A)

Big Mac prices, converted to a common currency, were cheaper.

B)

PPP cannot be computed in this manner because diets in lower-income nations do

not include fast food.

C)

Big Mac prices, converted to a common currency, were more expensive.

D)

lower-income workers could not afford to purchase fast food.

Page 5

21.

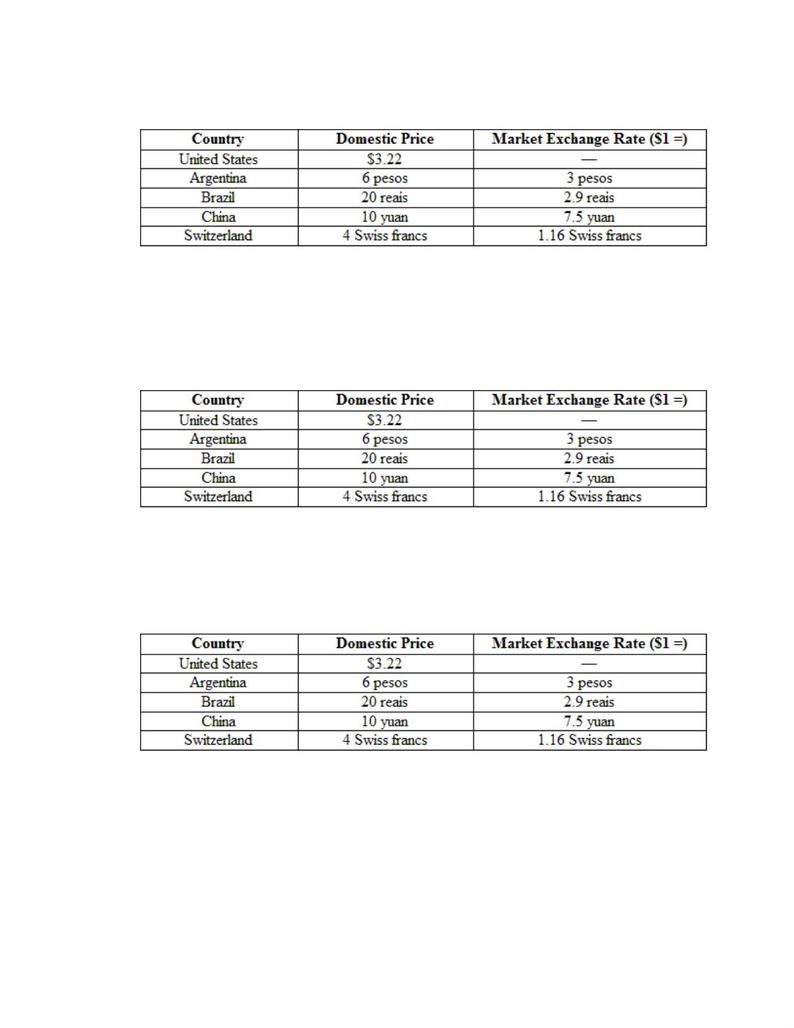

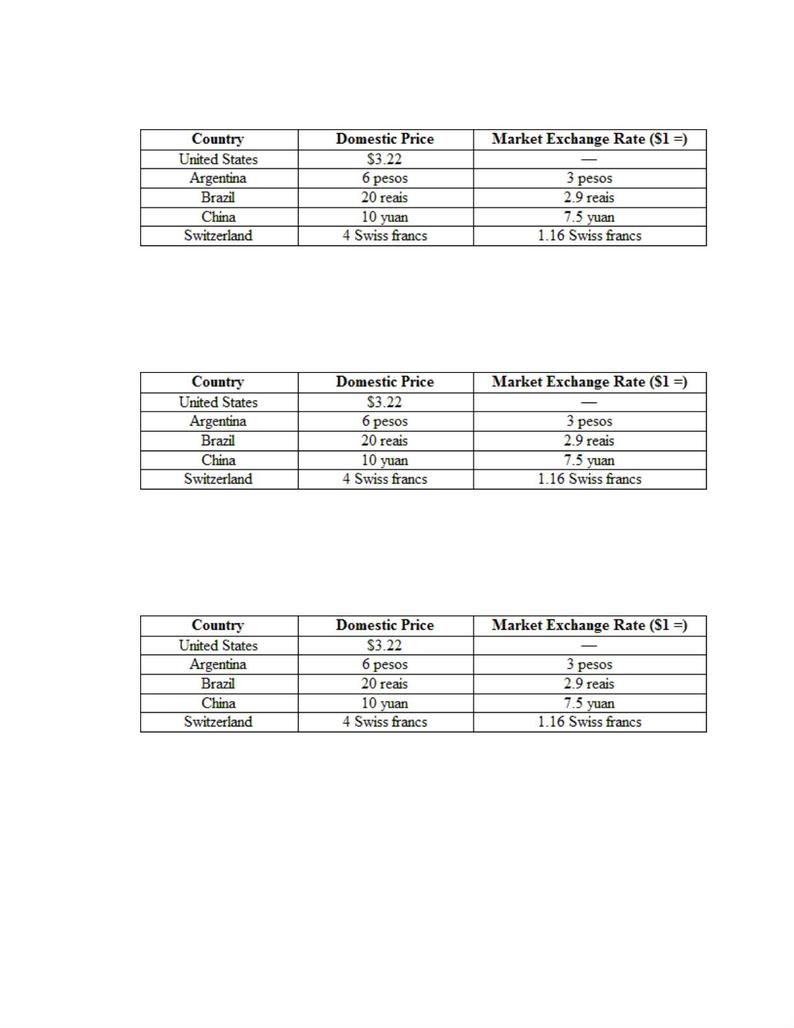

(Table: The Big Mac Index) The price of a hamburger in dollar terms is _____ in China

and _____ in Brazil.

A)

$2; $9.

B)

$1.33; $6.89

C)

$1.25; $6

D)

$6.89; $1.33

22.

(Table: The Big Mac Index) The price of a hamburger in dollar terms is ______ in

Argentina and _______ in Switzerland.

A)

$2; $3.45

B)

$3.45; $2

C)

$1.33; $2

D)

$2; $1.33

23.

(Table: The Big Mac Index) The PPP exchange rate for China should be _____ yuan.

A)

4

B)

3.1

C)

5

D)

32.2

Page 6

24.

(Table: The Big Mac Index) The PPP exchange rate for Brazil is ______ reais and

Switzerland is ______ Swiss francs.

A)

8; 1.24

B)

6.2; 1.24

C)

2.9; 1.16

D)

3.1; 2

25.

(Table: The Big Mac Index) The cheapest burger can be found in:

A)

Switzerland.

B)

Brazil.

C)

China.

D)

Argentina.

26.

(Table: The Big Mac Index) The most expensive burger is sold in:

A)

the United States.

B)

Brazil.

C)

China.

D)

Switzerland.

Page 7

27.

An interesting conclusion from many studies of international price differences is that:

A)

prices tend in general to be higher in low-income nations, causing steep declines in

their standards of living.

B)

on average, prices of traded goods in low-income nations are lower and, therefore,

their overall price levels are lower.

C)

on average, prices of nontraded goods in low-income nations are lower, but the

prices on traded goods are higher and, therefore, their overall price level is not

affected.

D)

price differences tend to be larger, depending on whether the central bank pegs the

nation's currency to the U.S. dollar or the Japanese yen.

28.

Deviations from purchasing power parity can be explained by the Balassa–Samuelson

model, which assumes:

A)

government regulation is absent.

B)

traded goods have the same prices, productivity in traded goods determines wages,

and wages determine prices of nontraded goods.

C)

worker productivity is rising, returns to capital equal the real rate of interest, and

there is no money illusion.

D)

competitive markets, full information, and full employment of resources.

29.

For a product that is traded internationally, with low trade costs, such as a DVD player,

competition dictates that workers involved in manufacturing that good will:

A)

probably not get the full value of their marginal products.

B)

earn higher wages if trade does not force them to compete with low-cost foreign

workers.

C)

earn wages that are determined by their productivity.

D)

lose their jobs if there are higher international product standards.

30.

The United States and China can produce TVs at $200 and 2000 yuan each. One day of

labor is needed to produce a TV in the United States and 10 days of labor are needed to

produce a TV in China. Each country also produces the nontraded good, car washing. In

each country, one car can be washed in one day. The exchange rate is 10 yuan = $1.

If trade costs are zero, what is the Chinese daily wage?

A)

2000 yuan

B)

667 yuan

C)

200 yuan

D)

25 yuan

Page 8

31.

The United States and China can produce TVs at $200 and 2000 yuan each. One day of

labor is needed to produce a TV in the United States and 10 days of labor are needed to

produce a TV in China. Each country also produces the nontraded good, car washing. In

each country, one car can be washed in one day. The exchange rate is 10 yuan = $1.

If trade costs are zero, what is the daily wage in the United States?

A)

$2000

B)

$200

C)

$100

D)

$150

32.

The United States and China can produce TVs at $200 and 2000 yuan each. One day of

labor is needed to produce a TV in the United States and 10 days of labor are needed to

produce a TV in China. Each country also produces the nontraded good, car washing. In

each country, one car can be washed in one day. The exchange rate is 10 yuan = $1.

What is the price of a car wash in the United States?

A)

$200

B)

$100

C)

$50

D)

$10

33.

The United States and China can produce TVs at $200 and 2000 yuan each. One day of

labor is needed to produce a TV in the United States and 10 days of labor are needed to

produce a TV in China. Each country also produces the nontraded good, car washing. In

each country, one car can be washed in one day. The exchange rate is 10 yuan = $1.

What is the price of a car wash in China?

A)

2,000 yuan

B)

1,000 yuan

C)

600 yuan

D)

200 yuan

Page 9

34.

The United States and China can produce TVs at $200 and 2000 yuan each. One day of

labor is needed to produce a TV in the United States and 10 days of labor are needed to

produce a TV in China. Each country also produces the nontraded good, car washing. In

each country, one car can be washed in one day. The exchange rate is 10 yuan = $1.

What is the ratio of U.S. to Chinese daily wages, with both expressed in dollars at the 10

yuan = $1 exchange rate?

A)

10

B)

20

C)

5

D)

1

35.

The United States and China can produce TVs at $200 and 2000 yuan each. One day of

labor is needed to produce a TV in the United States and 10 days of labor are needed to

produce a TV in China. Each country also produces the nontraded good, car washing. In

each country, one car can be washed in one day. The exchange rate is 10 yuan = $1.

Assume people in each country spend half their income on TVs and half on car washes.

Compute the consumer price index (CPI) for each country given by the square root of

the TV price times the car wash price. Convert the Chinese CPI to dollars at the 10 yuan

= $1 exchange rate. What is the ratio of the U.S. to Chinese CPI?

A)

10

B)

3.16

C)

5

D)

20

36.

The Balassa–Samuelson model says that wages and prices in general are higher in

higher-income nations because:

A)

they have more effective laws protecting their workers.

B)

the workers have a higher productivity level, which is reflected in prices of

nontraded goods.

C)

there is less competition in these economies.

D)

taxes on business and for entitlement programs raise labor and other costs, making

prices much higher.

37.

Country A has higher productivity in traded goods production than country B. The

difference between country A's and country B's overall price levels will widen as the

share of:

A)

nontraded goods in country A's consumption falls.

B)

traded goods in country A's consumption rises.

C)

nontraded goods in country A's consumption rises.

D)

nontraded goods in country B's consumption falls.

Page 10

38.

Country A is experiencing productivity growth. When compared with other countries

with lower productivity growth, we expect to see wages and incomes _______ and its

exchange rate _______.

A)

fall; appreciate

B)

rise, appreciate

C)

fall; depreciate

D)

rise; depreciate

39.

The percentage change in the real exchange rate between two nations is equal to the:

A)

product of home worker productivity and foreign productivity divided by the share

of traded goods in production.

B)

difference between home and foreign worker productivity.

C)

difference in the relative wage of foreign and home workers times the price level in

the nation.

D)

change in the difference between foreign worker productivity and home worker

productivity multiplied by the share of nontraded goods in total production.

40.

The Balassa–Samuelson effect states that when a nation's productivity rises relative to

its trading partners, its wages and prices rise and its real exchange rate:

A)

depreciates.

B)

converges to 1.

C)

appreciates.

D)

exhibits instability over a short period.

41.

We can calculate the changes in the real exchange rate necessary for purchasing power

parity by:

A)

the share of nontraded goods divided by the share of traded goods.

B)

the share of nontraded goods multiplied by the change in foreign traded

productivity level relative to home.

C)

nontraded goods minus domestic worker productivity.

D)

wages earned in nontraded goods industries divided by wages earned in traded

goods industries.

42.

In equilibrium, according to the Balassa–Samuelson effect, the real exchange rate is:

A)

always equal to 1.

B)

never equal to 1.

C)

often equal to 1.

D)

not necessarily equal to 1.

Page 11

43.

If the real exchange rate is higher (FX costs more) than the equilibrium exchange rate

(calculated according to the Balassa–Samuelson effect), the nation's currency is said to

be:

A)

undervalued.

B)

overvalued.

C)

at the proper level.

D)

at greater risk for a currency crisis.

44.

The Balassa–Samuelson effect can be used to forecast changes in real exchange rates by

considering the speed of ______ and ______.

A)

convergence to equilibrium; trend changes in the equilibrium value

B)

adjustment to trade imbalances; budget deficit reduction

C)

innovation and productivity; the deterioration of the peg

D)

adjustment to imbalances in income levels; educational attainment

45.

When PPP holds, the Balassa–Samuelson forecast is:

A)

very useful in predicting real and nominal exchange rate changes.

B)

somewhat useful except that traders are often unpredictable.

C)

not useful because when PPP holds, the real exchange rate is equal to 1.

D)

used only for comparisons between low-income nations.

46.

Suppose that the half-life of deviations from PPP is five years (it takes five years for the

difference between the actual and equilibrium real exchange rate to narrow by half) and

the nontraded share of consumption is 0.50. What will be the annual rate of change of

the real exchange rate if a country initially has a 20% gap between its actual and

equilibrium real exchange rates and its GDP is growing 5% faster than GDP in the rest

of the world?

A)

70%

B)

22%

C)

4.5%

D)

2.0%

47.

The Balassa–Samuelson forecast can be used to predict changes in _____ over time and,

therefore, can be used to predict ______ by adding in inflation changes.

A)

income levels; real GDP growth rates

B)

expectations; technology improvements

C)

real GDP; unemployment rates

D)

real exchange rates; nominal exchange rates

Page 12

48.

The formula for predicting changes in the nominal exchange rate, when PPP doesn't

hold, is the rate of real depreciation:

A)

multiplied by the nominal wage.

B)

multiplied by the interest rate differential.

C)

added to the inflation differential.

D)

multiplied by inflation in the home nation.

49.

Many analysts believe that China's currency (the yuan) is undervalued in real terms.

China has been experiencing a high rate of productivity growth. What would you expect

to happen to Chinese GDP and Chinese prices relative to U.S. prices if this pattern

continues over time?

A)

Chinese GDP will rise and Chinese prices will fall relative to U.S. prices.

B)

Chinese GDP will rise and Chinese prices will rise relative to U.S. prices.

C)

Chinese GDP will fall and Chinese prices will fall relative to U.S. prices.

D)

Chinese GDP will fall and Chinese prices will rise relative to U.S. prices.

50.

When a nation's currency is different from equilibrium, it is either overvalued or

undervalued. To restore equilibrium, either a ____ or ____ must occur.

A)

return to a balanced budget; more government belt-tightening

B)

nominal exchange rate change; a change in the nation's price level

C)

national cut of imports; a national increase of exports

D)

national cut of exports; a national increase of imports

51.

The Balassa–Samuelson model about exchange rates suggests that if the Brazilian real is

undervalued by 44%, it would take ____ years for the real to appreciate by half of the

original amount of undervaluation at the rate of ___ per year.

A)

5; 4.4

B)

4; 5.5

C)

1; 22

D)

3; 7

52.

The Balassa–Samuelson forecast applied to China during 2000–04:

A)

failed to predict the slow rise in the exchange rate that actually occurred.

B)

failed to predict the Chinese inflation that actually occurred.

C)

failed to predict the rise in Chinese real GDP that actually occurred.

D)

predicted correctly that the slow appreciation of the Chinese exchange rate would

result in higher inflation of the Chinese yuan.

Page 13

53.

The Balassa–Samuelson forecast predicted that Argentina's overvalued exchange rate

would have to be offset by:

A)

maintaining a more credible peg to the U.S. dollar.

B)

a combination of more intense price deflation in Argentina relative to the United

States and an exchange rate depreciation.

C)

intervention by the IMF to stabilize the peso.

D)

a trade embargo coupled with capital controls.

54.

If a country's currency is overvalued in real terms, what combination of exchange rate

and price changes will cause its exchange rate to move toward its real equilibrium

value?

A)

currency depreciation and deflation

B)

currency depreciation and inflation

C)

currency appreciation and deflation

D)

currency appreciation and inflation

55.

Slovakia experienced rapid productivity growth and an undervalued exchange rate

during 1992–2004, which presented a dilemma because:

A)

its performance put it below the standards for European Union membership.

B)

its government did not understand how to inflate Slovakia's own currency.

C)

real GDP growth suffered as predicted by Balassa–Samuelson.

D)

to keep its nominal exchange rate from appreciating against the euro (required for

Eurozone membership), Slovakia would have had to experience higher inflation as

per the Balassa–Samuelson effect.

56.

By stabilizing their exchange rates to join the Eurozone, the Baltic states have seen:

A)

lower inflation.

B)

faster price growth.

C)

massive budget deficits.

D)

faster price growth and massive budget deficits.

57.

If UIP holds, then returns on foreign investments (the carry trade) would be:

A)

greater than 10%.

B)

equal to the return from investment plus the appreciation of the home currency.

C)

equal to the return from investment minus appreciation of the home currency.

D)

equal to the reciprocal of the appreciation of the home currency.

Page 14

58.

For the time period between 1992 and 2001, an investor who borrowed Japanese yen at

low interest rates and invested in Australian dollar assets at higher interest rates:

A)

enjoyed an overall profit because the interest differential was higher than the net

exchange appreciation of the yen.

B)

suffered substantial losses because the interest differential was lower than the net

exchange appreciation of the yen.

C)

experienced offsetting positive and negative returns because of long-run swings in

the exchange rate.

D)

did not realize that, as a result of transactions costs and taxes, any net return would

be zero.

59.

If the interest rate is 1% in Japan and 9% in Australia, then:

A)

we can expect the interest rates to equalize.

B)

investors will buy Japanese bonds.

C)

the yen will depreciate by 8%.

D)

the yen will appreciate by 8%.

60.

According to the text, the carry trade strategy of borrowing yen and investing in

Australian dollars:

A)

never resulted in positive profits between 1982 and 2001.

B)

produced roughly offsetting profits and losses between 1992 and 2001.

C)

produced large profits between 1992 and 2001.

D)

produced large losses between 1992 and 2001

61.

Between 1992 and 2001, the carry trade strategy of borrowing yen and investing in

Australian dollars produced roughly offsetting profits and losses because:

A)

the yen appreciated whenever the Australian–Japanese interest rate differential

widened.

B)

the yen depreciated whenever the Australian–Japanese interest rate differential

widened.

C)

the yen appreciated whenever the Australian–Japanese interest rate differential

narrowed.

D)

the value of the yen against the Australian dollar remained constant.

62.

Many ordinary Japanese workers are investing any extra funds in U.S. dollar and other

investments. Why?

A)

They fear a decline in the Japanese economy and that they will lose their jobs.

B)

They experience higher interest rates not offset by yen appreciation.

C)

Many desire to emigrate to the United States and want to establish a financial

presence.

D)

They have access by computer to U.S. investment houses that do not exist in Japan.

Page 15

63.

If a nation maintains fixed exchange rates, it may be a haven for foreign investment if:

A)

investors (irrationally fearing the peg will not hold) demand higher interest rates

(risk premium) on investments denominated in the currency.

B)

investors make more money when they go against conventional wisdom and put

money in riskier investments.

C)

there is more certainty over the real return on investments.

D)

its government taxes returns from those investments.

64.

Why did investors not believe that Argentina's peg to the U.S. dollar during the 1990s

was credible?

A)

Over most of this period, Argentine interest rates were higher than U.S. interest

rates.

B)

Over most of this period, Argentine interest rates were lower than U.S. interest

rates.

C)

Over most of this period, Argentine interest rates were equal to U.S. interest rates.

D)

Over most of this period, Argentine interest rates had no relationship to U.S.

interest rates.

65.

If a country has a credible peg with no risk of a depreciation or of other risks (e.g.,

default risk), then UIP implies that:

A)

its interest rate should equal foreign interest rates.

B)

its interest rate should be greater than foreign interest rates.

C)

its interest rate should be less than foreign interest rates.

D)

there should be no relationship between its interest rate and foreign interest rates.

66.

Uncovered interest parity implies that interest arbitrage will:

A)

earn a premium.

B)

earn less than a normal return.

C)

not be possible.

D)

end up raising real rates of interest.

67.

The existence of profits from the carry trade seems to negate the notion of uncovered

interest parity (UIP), but:

A)

UIP has never really been proved to exist.

B)

UIP occurs over longer periods (perhaps two years) as a result of long and volatile

movements in the exchange rate.

C)

if uncovered interest parity exist, carry trade profits would be higher still.

D)

carry trade profits are not related to changes in the nominal rate of interest.

Page 16

68.

When carry trade speculation grows to high levels, it can affect the economy. How?

A)

It is a stabilizing factor.

B)

It can be a destabilizing factor, causing large swings in exchange rates.

C)

It creates large differentials in income distribution in emerging markets.

D)

Inflation is always a problem when carry trade activity increases.

69.

Because interest returns are known ex ante, the only unknown factor in the carry trade

(international investments) is:

A)

government tax policy.

B)

default risk.

C)

exchange rate risk (forecast error).

D)

climate change risk.

70.

Even though UIP is shown to hold within a small range on average, some deviations

allow systematic profits to be made. This violates all of the following principles,

EXCEPT:

A)

rational expectations with no systematic bias.

B)

efficient markets hypothesis, which postulates that all traders are operating with the

same information.

C)

random deviations in exchange rates around their mean.

D)

rational expectations with systematic bias.

71.

Argentina's 2001 currency crisis illustrates that:

A)

a peg cannot survive major domestic default and banking crises.

B)

a peg can be relied on as long as it is tied to a major world currency, such as the

U.S. dollar.

C)

a peg is the best choice for many emerging market economies.

D)

even if a peg breaks, foreign investors can recoup losses from the government.

72.

What is the "peso problem"?

A)

Expectations are realized on average, and returns from interest arbitrage are zero.

B)

Even when exchange rates are fixed, investors often demand a premium for interest

arbitrage, so the return from arbitrage can be positive or negative.

C)

Pegged currencies are less stressful for investors because there is no room for

speculation.

D)

Returns from interest arbitrage are always positive, even when the peg breaks.

Page 17

73.

A forecast error is caused by a:

A)

real exchange rate depreciation.

B)

nominal exchange rate depreciation.

C)

difference between expected nominal exchange rate depreciation and actual

depreciation.

D)

nation's movement fixed to floating exchange rates.

74.

Actual carry trade profits which are based on actual expected depreciation indicate that:

A)

uncovered interest parity does not hold systematically, and on average the carry

trade is profitable.

B)

uncovered interest parity holds, and there is no possibility of profitable interest

arbitrage.

C)

purchasing power parity is the best indicator of future currency depreciation.

D)

profits in the carry trade are not taxed, which is a burden for emerging market

economies.

75.

The existence of systematic profits in the carry trade seems to violate which of the

following?

A)

the principle of reason

B)

the efficient markets hypothesis combined with UIP and rational expectations

C)

the principle of second best

D)

the principle of "two out of three"

76.

When trade costs are small, the effect on trades in financial markets:

A)

is usually quite substantial.

B)

is usually quite small and would not interfere with interest arbitrage.

C)

might cause investors to delay their reaction to a profitable opportunity.

D)

causes a bias toward trades in higher-income nations with more developed

financial markets.

77.

Analysts have puzzled over why carry trade profits persist. They have rejected all the

following explanations, EXCEPT:

A)

trade costs in financial markets are sufficiently high enough to make arbitrage

impossible.

B)

when traders buy or sell an asset in large volumes, it may move the price

sufficiently to cause independent changes in the exchange rate.

C)

risk of exchange rate movements is so large that many traders prefer not to engage

in arbitrage in these markets for fear of excessive losses.

D)

there may be a substantial difference in the bid-ask prices of currency that make

arbitrage less profitable.

Page 18

78.

An analysis of profits in the carry trade revealed a predictable profit (+)/loss (–) of:

A)

+25%.

B)

+0.08%.

C)

–0.02%.

D)

–0.2%.

79.

The ratio of the returns on an asset to the risks taken on by investors is known as:

A)

the Marshall–Leamer theorem.

B)

the price-to-earnings ratio.

C)

the Sharpe ratio.

D)

the standard deviation from zero.

80.

Investors' decisions to invest in a risky asset can be analyzed by using the Sharpe ratio,

which measures the:

A)

home interest rate plus the inflation differential minus home exchange rate

depreciation.

B)

difference in nominal interest rates divided by the change in the foreign nominal

interest rate.

C)

mean of the difference in returns divided by the standard deviation of the

differences.

D)

ratio of exchange rate depreciation between home and foreign.

81.

A foreign exchange trader indicates that he or she can make a predictable return of 10%

per year in carry trade between Japanese yen and Australian dollars with a standard

deviation of 50%. What is the Sharpe ratio for this carry trade?

A)

500%

B)

50%

C)

20%

D)

10%

82.

Many conservative investors require Sharpe ratios of at least ________ to warrant

undertaking riskier investments.

A)

10%

B)

25%

C)

50%

D)

75%

Page 19

83.

If the Sharpe ratio for interest arbitrage situations is low, how may this explain why

traders shun available profits and why UIP may not hold?

A)

The ratio of rewards to risk is below the threshold required for investors.

B)

Investors know that in the long run, their returns will be close to zero.

C)

Investors are extremely risk averse.

D)

There are known limits to arbitrage profits.

84.

Many economists conclude that, although there may be predictable excess returns from

risky arbitrage in foreign exchange markets, the reward-risk ratio:

A)

is too low to attract additional investors.

B)

is too high to attract additional investors.

C)

varies too much to attract additional investors.

D)

is too random to attract additional investors.

85.

The theory of carry trade profits focuses on the reward-risk ratio. Analysts believe

profits from the carry trade exist because:

A)

once the big profits have been taken, the remaining profits are too small for the

level of risk undertaken.

B)

the larger the reward, the smaller the risk.

C)

investors will only seek returns that carry no risk.

D)

the market has been saturated with too much financial trading, and it needs to settle

down before investors would be willing to try again.

86.

The reward-risk ratio theory has gained credence because of evidence that when carry

trade profit margins are high, arbitrage bids them down quickly, whereas when they are

low:

A)

investors pursue them more slowly.

B)

investors are often not interested.

C)

arbitrage bids them up quickly.

D)

no arbitrage is possible.

87.

Excessive debt might lead a nation to consider default as an option if:

A)

the international court of justice is not meeting.

B)

it has no real assets to sell.

C)

repayment is more painful than the costs of default.

D)

the other nations do not threaten military action.

Page 20

88.

Nations must consider the costs of default when choosing a course of action.

Economists group these costs into:

A)

short run and long run.

B)

internal and external.

C)

financial market penalties and macroeconomic costs.

D)

monetary and real.

89.

A nation often has an option to default on its sovereign debt rather than undergo painful

repayment because:

A)

in every debt agreement there is an escape clause.

B)

there is no international debt court, nor would creditors gain advantage by military

action against debtors.

C)

the finance ministers have the option to choose to repay or deliver commodities in

lieu of payment.

D)

there are limited means by which to transfer international wealth, such as gold or

domestic stocks or bonds.

90.

Nations that are considering default rather than restructuring or repayment face costs.

Which of the following is NOT a cost of default?

A)

the ability to enjoy the use of the borrowed funds without the pain of repayment

B)

exclusion from credit markets, which can cause a reduction in consumption

C)

lost opportunity to invest or purchase needed imports for trade

D)

higher risk premiums for all borrowers and financial disruption

91.

Which of the following facts about sovereign debt is FALSE?

A)

There is no legal recourse to debt repayment.

B)

Debtors are never forced to repay the debt.

C)

Military option is available to make the country repay its debt.

D)

Military option is not available to make the country repay its debt.

92.

Among the penalties that hurt countries trying to default on their loans is:

A)

higher interest rates and fewer loan opportunities in the future.

B)

improved trade volume.

C)

higher growth in GDP.

D)

lower risk premiums on loans.

Page 21

93.

If a nation's leaders make rational decisions, they would weigh the costs and benefits of

defaulting on the debt as follows if the:

A)

borrowing costs are greater than the repayment costs, the borrower will not default.

B)

nation's consumption after repayment of principal and interest exceed the

consumption available after default costs are deducted, the nation will repay.

C)

nation can borrow from other lenders more cheaply, it will simply refinance and

deal with the problem later.

D)

nation can sell off assets and increase the workweek to export more, it will

definitely repay.

94.

A nation will choose repayment over default if:

A)

taxes would be higher after repayment than default.

B)

interest rates would grow to uncomfortably high levels.

C)

domestic consumption after repayment is higher than domestic consumption after

default.

D)

the level of reserves (gold and foreign currency) would be lower after default than

after repayment.

95.

If the debt payoff amount ([1 + rL]L) is smaller than the punishment cost of default (cY),

a nation will:

A)

default.

B)

seek to delay repayment until its interest cost declines.

C)

repay in full.

D)

find another lender who will refinance.

96.

If a nation has default costs (punishment costs) = c, as a percent of GDP, every extra

dollar paid toward the debt is equivalent to:

A)

a dollar's saving in interest over time.

B)

giving more income to the creditors.

C)

a loss of consumption of (1 – c) dollars.

D)

raising the burden of the debt by 1/(1 – c) dollars.

97.

An emerging economy as a current GDP of $100 billion. It borrows $20 billion at a real

interest rate of 5%, which it will repay next year. The costs of default are 25% of GDP.

Suppose that the country's GDP falls to $80 billion next year. Which of the following is

a correct assumption?

A)

It will repay the loan.

B)

It will default on the loan.

C)

It will be indifferent toward repaying or defaulting on the loan.

D)

Not enough information is provided to answer the question.

Page 22

98.

An emerging economy as a current GDP of $100 billion. It borrows $20 billion at a real

interest rate of 5%, which it will repay next year. The costs of default are 25% of GDP.

What is the country's repayment threshold level of GDP (i.e., the GDP at which it is

indifferent between defaulting and repaying the loan)?

A)

$75 billion

B)

$95 billion

C)

$84 billion

D)

$76 billion

99.

An emerging economy as a current GDP of $100 billion. It borrows $20 billion at a real

interest rate of 5%, which it will repay next year. The costs of default are 25% of GDP.

Suppose that the country's GDP rises to $110 billion next year. What will be the value

of its consumption if it defaults on the loan?

A)

$75 billion

B)

$82.5 billion

C)

$89 billion

D)

$110 billion

100.

An emerging economy as a current GDP of $100 billion. It borrows $20 billion at a real

interest rate of 5%, which it will repay next year. The costs of default are 25% of GDP.

At the GDP level of $110 billion, what will be the country's consumption if it repays the

loan?

A)

$75 billion

B)

$82.5 billion

C)

$89 billion

D)

$110 billion

101.

An emerging economy as a current GDP of $100 billion. It borrows $20 billion at a real

interest rate of 5%, which it will repay next year. The costs of default are 25% of GDP.

Suppose that the real rate of interest rises from 5% to 7.5%. With the country's GDP

level of $110 billion, what will happen to the threshold level of GDP?

A)

The threshold level of GDP will rise.

B)

The threshold level of GDP will fall.

C)

The threshold level of GDP will remain constant.

D)

Not enough information is provided to answer the question.

Page 23

102.

The factors that affect the probability of a nation's repayment versus default include the:

A)

exchange rate of its currency with that of the lender and whether the lender is

private or official.

B)

conditions set out in the original loan agreement plus the percent of the population

in the workforce.

C)

ability to earn export revenues and the nation's past credit history.

D)

volatility of its output and how burdensome the debt repayment is.

103.

A higher lending rate or an increase in debt principal increases the probability of default

because:

A)

creditors get more anxious to get repaid and therefore drive debtors into

bankruptcy.

B)

the nation's repayment/default threshold is higher because the consumption level

after repayment of principal and interest falls, whereas the default cost did not

change.

C)

the bankers of the nation will not help because they can make more profitable loans

to third-party borrowers.

D)

the government is adverse to repaying a debt that has existed for more than five

years.

104.

An increase in the volatility of GDP increases the probability of default because:

A)

it increases political tension and there is a big turnover in government officials who

don't know how to run the financial system.

B)

automatic stabilizers kick in and increase spending when GDP is lower, taking

money away from repaying debt.

C)

tax receipts are erratic and government is not good at coming up with payments

when they are due.

D)

there is still only one potential real GDP level but many more possibilities below

potential real GDP, thus a higher likelihood of default.

105.

The GDPs of two emerging economies (A and B) are equal, but GDP in country B is

less volatile than GDP in country A. Both have borrowed $25 billion that must be repaid

next year. Which of the following is correct in terms of the probabilities of default?

A)

Both A and B have the same probability of default.

B)

A's probability of default is higher than B's probability of default.

C)

B's probability of default is higher than A's probability of default.

D)

Based on probability, B will default.

Page 24

106.

The GDPs of two emerging economies (A and B) are equal, but GDP in country B is

less volatile than GDP in country A. A has borrowed $X to be repaid next year, and B

has borrowed $Y to be repaid next year. Assume that A and B have equal probabilities

of default on their borrowing. Which of the following must be correct?

A)

$X is greater than $Y.

B)

$X = $Y.

C)

$X is less than $Y.

D)

$X is significantly greater than $Y.

107.

The breakeven condition for a lender to an emerging market economy where the risk of

default is positive cannot exceed the:

A)

probability of repayment minus the probability of default times the rate of interest

(r × [pR – pD]).

B)

probability of default times the probability of repayment (pD × pR).

C)

lender's cost, which is the probability of repayment, times the lender's interest

earnings (p × [1 + RL]).

D)

market rate of interest for the most default-prone borrowers.

108.

A study done on the average return (after all costs and defaults were figured in) revealed

that creditors lending to low-income nations:

A)

on average earned substantially higher returns.

B)

on average earned less than the return on less risky lending.

C)

on average earned only a slight risk premium, overall just breaking even.

D)

had on average negative returns.

109.

Evidence on developing countries' debt suggests that lenders have:

A)

consistently made huge profits by lending money to these countries.

B)

engaged in predatory lending practices.

C)

at best broken even by lending to these countries.

D)

done much worse on their investments to advanced countries.

Page 25

110.

To determine the supply of lending to low-income nations, we calculate expected

returns, which depend on the probability of repayment. The probability is related in the

following way to various factors.

A)

The probability is positively correlated to the size of total debt and to the volatility

of GDP.

B)

The probability is positively correlated to the size of total debt and negatively to

the volatility of GDP.

C)

The probability is negatively correlated to the size of total debt and positively to

the volatility of GDP.

D)

The probability is negatively correlated to the size of total debt and to the volatility

of GDP.

111.

At some level of lending, the interest rate at which lenders are willing to supply loans to

an emerging market economy will begin to increase as the:

A)

economy's total loans increase.

B)

economy's GDP increases.

C)

economy's default risk decreases.

D)

volatility of the economy's GDP decreases.

112.

If an emerging market economy has a low level of international debt, it can expect to

borrow at the world interest rate:

A)

on risk-free debt.

B)

plus a risk premium.

C)

minus a risk premium.

D)

plus a risk and inflation premium.

113.

Ceteris paribus, if the volatility of an emerging market economy's GDP increases:

A)

it will not be able to borrow as much as before at the world interest rate on risk-free

debt.

B)

it will be able to borrow more than before at the world interest rate on risk-free

debt.

C)

it can borrow the same amount as before at the world interest rate on risk-free debt.

D)

its risk premium falls.

114.

A nation will borrow as long as:

A)

the benefit of consumption smoothing insurance derived from borrowing is greater

than the cost of borrowing those funds.

B)

the supply of domestic credit is equal to the demand for domestic credit.

C)

international creditors will lend to it at lower-than-market rates.

D)

the nation still has foreign currency reserves to calm anxious creditors.

Page 26

115.

Suppose that an emerging market economy was paying the world interest rate on

risk-free debt (5%) plus a risk premium of 2% on its international debt. For some

reason, the volatility of its GDP increases. Ceteris paribus, how will the increased GDP

volatility affect the interest rate it will pay on future borrowing?

A)

The interest rate will fall.

B)

The interest rate will rise.

C)

The interest rate will be unaffected.

D)

The interest rate will first fall, then rise as it repays its debt.

116.

When GDP volatility increases, it changes the equilibrium in the credit market for

sovereign borrowers. How?

A)

Volatility increases the probability that a nation will repay and decreases the need

to borrow, so the equilibrium debt level and interest rates drop.

B)

Volatility decreases the probability that a nation will repay and increases the need

to borrow, so the equilibrium debt level is indeterminate and interest rates rise.

C)

Volatility decreases the probability that a nation will repay and decreases the need

to borrow, so the amount of debt level will fall and interest rates drop.

D)

Volatility increases the probability that a nation will repay and increases the need

to borrow, so the amount of debt level and interest rates rise.

117.

All but one of the following are international financial market penalties that defaulters

must face. Which is NOT a financial market penalty?

A)

denial of access to international credit markets for some time

B)

increases in risk premiums on their future international borrowing

C)

increases in the domestic money supply while inflation is occurring

D)

an inability to borrow internationally in their own currencies

118.

Argentina defaulted on its international debt and the Argentine peso depreciated by

more than two-thirds in 2001. Why would you expect that, in 2007, most lenders will

only make loans to Argentina that are denominated in dollars, euros, or a currency other

than the Argentine peso?

A)

Lenders fear that another default will be accompanied by a significant depreciation

of the Argentine peso.

B)

Lenders fear that another default will be accompanied by a significant appreciation

of the Argentine peso.

C)

In case of a default, lenders will always be repaid if the loans are

dollar-denominated than peso-denominated.

D)

In the case of a default, lenders are less likely to be repaid if the loans are

Argentine peso-denominated.

Page 27

119.

Which of the combinations of default, exchange rate, and banking crises occurred most

frequently between 1970 and 2000?

A)

default crisis only

B)

default and exchange rate crises

C)

default and banking crises

D)

default, exchange rate, and banking crises

120.

What was the approximate average annual cost for a country suffering from default,

banking, and exchange rate crises simultaneously during the period 1970 to 2000?

A)

2% of GDP per year

B)

12% of GDP per year

C)

22% of GDP per year

D)

92% of GDP per year

121.

Prior to the 2007–09 financial crisis, the world saw:

A)

an increase in investment demand.

B)

a decrease in savings.

C)

an increase in real interest rates.

D)

an increase in savings.

122.

The savings glut was likely caused by all of the following, EXCEPT a:

A)

deficit in the fast-growing advanced countries.

B)

surplus in slow-growing advanced countries.

C)

surplus in emerging Asian economies.

D)

deficit in petroleum-exporting countries.

123.

The recent downward trends in interest rates worldwide could be attributed to:

A)

tariffs and other nontariff trade barriers.

B)

economic sanctions.

C)

a savings glut.

D)

excess consumption in developed nations.

124.

Some groups of nations have experienced surplus in their CAs for several years,

whereas for others the surplus is temporary. Within what groups of nations are surplus

nations included?

A)

slow-growth advanced economies with high savings rates, oil-exporting nations,

and most of Asia

B)

sub-Saharan African nations, the Indian continent, and the Nordic countries

C)

Argentina, Chile, and Brazil, as well as several Central American nations

D)

Ireland, Spain, and Portugal

Page 28

125.

In the decade preceding the financial crisis, as growing emerging market economies

began to realize current account surpluses due to very high rates of saving, they

channeled investment from _____ to ______.

A)

the United States; Russia

B)

rich nations; poor nations

C)

their own economies; developed market economies

D)

high-yield assets; low-yield assets

126.

Following the severe contraction following the East Asian financial crisis in the late

1990s, many emerging market economies began to:

A)

cut unnecessary investment projects.

B)

"save" foreign currency export earnings by investing them in developed market

assets and holding higher levels of foreign currency reserves.

C)

borrow more when interest rates were lower, and repay when they are higher.

D)

make sure their foreign currency earnings were used to build capital in their own

economies.

127.

The flow of capital investment from emerging markets to developed markets resulted in:

A)

greatly reduced borrowing costs and created a huge wave of investment funds in

developed market economies.

B)

overpriced assets in the emerging market economies.

C)

increased political leverage for the emerging markets in developed economies.

D)

a decline of responsibility in the emerging markets as they relied on developed

economies for returns on investment.

128.

Lessons from the emerging market economies of the dangers of growing internal and

external debt _____ in the developed economies, causing ______.

A)

were taken into account; a more responsible use of borrowed funds

B)

were disregarded; extreme vulnerability to banking, default, and even currency

crises

C)

made their way into economic textbooks early on; newly trained economists to be

up to speed on the dangers of deficits and debt

D)

made a huge impression; people to increase saving and reduce borrowing

Page 29

129.

Contributing to the crisis may have been government failure for all of the following

reasons, EXCEPT:

A)

too many guarantees and subsidies to banks and quasi-official financial institutions

encouraging irresponsible lending.

B)

a monetary policy that was "too easy," resulting in low interest rates and excessive

borrowing.

C)

a trend toward deregulation and lack of oversight of financial innovation.

D)

a reversion to economic fundamentals such as balanced budgets and a paring down

of financial innovation.

130.

Money creation to support spending in the aftermath of the financial crisis was

ineffective because:

A)

there was not enough of it.

B)

banks, individuals, and firms used the additional liquidity to rebuild wealth by

paying down debt rather than spending.

C)

much of the money leaked out to overseas deposits.

D)

spending was growing too fast and people were using money substitutes.

131.

While the financial crisis was devastating in many ways, your textbook author says the

worst consequence is:

A)

low levels of output and high unemployment that could linger for several years.

B)

the inability of banks to borrow.

C)

the difficulty of conducting monetary policy in an era of increased regulation.

D)

some of the European peripherals had to come to the rescue of the United States.

132.

The global recession following the financial crisis hurt the weaker Eurozone debtor

economies more because:

A)

their central banks, backed by ECB lending, had lent based on expected high

returns to investment that did not materialize.

B)

their governments had to pull out of the euro.

C)

their exchange rates depreciated.

D)

they had to cut their military forces to balance their budgets.

133.

Compared with the developed market economies that had borrowed heavily in the run

up to the financial crisis, the emerging market creditors:

A)

suffered much more because of borrowers who defaulted on loans.

B)

suffered much less because the governments in those nations raised taxes.

C)

fared well and recovered rapidly because they restricted borrowing and saving

foreign currency reserves.

D)

had to cut government spending and reduce money creation as austerity measures.

Page 30

134.

Explain why and how the existence of trade costs affects arbitrage.

135.

The LOOP and the existence of PPP depend on entities being able to trade without cost,

thereby moving prices. What are trade costs that limit arbitrage and prevent price

convergence?

136.

Briefly describe the insights of the Balassa–Samuelson model regarding deviations from

LOOP.

137.

How is the Balassa–Samuelson model useful in forecasting real exchange rates?

138.

Suppose a country is experiencing significant productivity growth of 5% relative to that

of another country with 2% productivity growth. Both countries have about 40% of their

consumption in nontraded goods. What does this imply about the rate at which the

exchange rate will change?

139.

The performance of the Australian dollar from 2002–07 illustrates which major points

about international investments?

140.

Explain the essence of the carry trade and why it is noteworthy.

141.

Explain the two types of costs associated with default on debt.

142.

How does output volatility affect the probability that a country will pay a loan (instead

of defaulting)?

143.

Suppose an emerging economy has a current GDP of $100 billion. Of this GDP,

consumption is 50% of it. The country borrows $20 billion at a real interest rate of 5%,

which it will repay next year. The costs of default are 25% of GDP. Will it repay or

default on the loan? Explain.

144.

How does output volatility affect the interest rate that a country will face if it chooses to

borrow in credit markets? Explain.

Page 31

145.

What financial market penalties exist for sovereign debt defaults? Describe and assess

these penalties in terms of maintaining discipline and consequences in the market for

international lending.

146.

The dilemma of choosing between the two paths of default or repayment, both of which

are very costly to the economy, is complex and risky. Discuss factors affecting a

nation's analysis of this topic.

147.

The default risk in higher-income nations seems lower than in lower-income nations.

Compare and discuss causes of any differences in the default risk.

148.

How did the emerging market crises in 1997 contribute to the global crisis in 2007–09?

149.

Interesting aspects of the aftermath of the financial crisis were the difficulties faced by

the developed market economies in restoring financial stability, shoring up the banking

system, preserving international payments and trade, and bringing GDP up to its former

level. Discuss several of these and draw appropriate conclusions.

Page 32

Answer Key

1.

B

2.

C

3.

A

4.

A

5.

D

6.

A

7.

D

8.

D

9.

B

10.

A

11.

B

12.

C

13.

C

14.

D

15.

A

16.

D

17.

A

18.

D

19.

C

20.

A

21.

B

22.

A

23.

B

24.

B

25.

C

26.

B

27.

B

28.

B

29.

C

30.

C

31.

B

32.

A

33.

D

34.

A

35.

B

36.

B

37.

C

38.

B

39.

D

40.

C

41.

B

42.

D

43.

A

44.

A

Page 33

45.

C

46.

C

47.

D

48.

C

49.

B

50.

B

51.

A

52.

D

53.

B

54.

A

55.

D

56.

B

57.

C

58.

C

59.

D

60.

B

61.

A

62.

B

63.

A

64.

A

65.

A

66.

C

67.

B

68.

B

69.

C

70.

D

71.

A

72.

B

73.

C

74.

A

75.

B

76.

B

77.

C

78.

B

79.

C

80.

C

81.

C

82.

C

83.

A

84.

A

85.

A

86.

B

87.

C

88.

C

89.

B

90.

A

Page 34

91.

C

92.

A

93.

B

94.

C

95.

C

96.

C

97.

B

98.

C

99.

B

100.

C

101.

A

102.

D

103.

B

104.

D

105.

B

106.

C

107.

C

108.

C

109.

C

110.

D

111.

A

112.

A

113.

A

114.

A

115.

B

116.

B

117.

C

118.

A

119.

D

120.

C

121.

D

122.

D

123.

C

124.

A

125.

C

126.

B

127.

A

128.

B

129.

D

130.

B

131.

A

132.

A

133.

C

134.

135.

136.

Page 35

137.

138.

139.

140.

141.

142.

143.

144.

145.

146.

147.

148.

149.